コモンマーモセット

この項目「コモンマーモセット」は途中まで翻訳されたものです。(原文:英語版 "Common marmoset" 20:13, 14 August 2015 (UTC)) 翻訳作業に協力して下さる方を求めています。ノートページや履歴、翻訳のガイドラインも参照してください。要約欄への翻訳情報の記入をお忘れなく。(2018年2月) |

| コモンマーモセット | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

コモンマーモセット Callithrix jacchus

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 保全状況評価[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

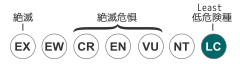

| LEAST CONCERN (IUCN Red List Ver.3.1 (2001))

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 分類 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 学名 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Callithrix jacchus (Linnaeus, 1758)[1][2][3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| シノニム | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 和名 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| コモンマーモセット[4][5][6][7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 英名 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common marmoset[2][8] White-tufted-ear marmoset[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

生息域

|

コモンマーモセット(Callithrix jacchus)は、霊長目(サル目)マーモセット科(キヌザル科)Callithrix属に分類される新世界ザルの一種である。Callithrix属の模式種。

マウスよりも人間に近い実験動物として利用される[9]。新世界ザルとしては初めて、全ゲノム配列が決定されている[10][11]。

もとは、ブラジルの北東沿海部、ピアウイ、パライバ、セアラ、リオグランデドノルテ、ペルナンブーコ、アラゴアス、そしてバイーア州に生息する[12]。飼育されていた個体が逃げたり、また飼育者が意図的に放獣した事により1920年代にはブラジル南部まで生息域を広げている。例えばリオデジャネイロでは、1929年に野生化で存在している事が見出されており、本来の生息域ではない地域では外来種として取り扱われている。特に、近縁種、例えばシロミミマーモセットCallithrix auritaとの交雑や鳥類の巣や卵を襲う事が問題になっている[13]。

生理学ならびに形態学的特徴[編集]

コモンマーモセットはサルとしては小型で、長い尾を特徴とする。オスとメスの大きさの差は小さいが、オスの方が若干大きい。体長はオスで平均188 mm (7.40 in)、メスで185 mm (7.28 in)、体重はオスで256 g (9.03 oz)、メスで236 g (8.32 oz)である[14]。体毛の色は多色で、茶色、灰色、黄色のものが混ざって存在している。耳は白い長い毛で覆われており、また尾には縞模様がある。顔は皮膚が露出し、前頭部には白い斑がある[15]。幼獣は茶色で、黄色い毛と耳の白い毛は後から発達してくる。

他のマーモセット属と同様、コモンマーモセットは鉤爪を持っている。例外は足の親指で、その指だけはその他の霊長類と同様平爪となっている。[16]マーモセットはリスのような樹上生活を送っており、樹に垂直に掴まったり、飛び移ったりする。また枝の上を四つ足で歩行する。[14][17]。鉤爪は、そのような行動様式に適応した結果だと考えられる。またマーモセット属と共通な特徴として、ノミのような形をした大きな切歯と食餌に適応した盲腸があげられる[14]

生息域と生態[編集]

コモンマーモセットの本来生息域はブラジル東部から中部にかけてである。しかし、その他の地域にもヒトの手により分布するようになり、リオデジャネイロ、アルゼンチンのブエノスアイレスにも見られる[18]。マーモセットは森林に広く分布する。大西洋に面した森林から、内陸の半落葉林、また、サバンナ森林や水系森林にも分布する[19]マーモセットは乾燥した二次森林や境界域にも適応している[17]。

食性[編集]

コモンマーモセットの鉤爪、切歯の形状、それから腸管は、植物の浸出物と昆虫食に特殊化していることを反映しているものと考えられている。コモンマーモセットは植物のガム、樹液、ラテックスや樹脂を食べる[17][19]。コモンマーモセットは鉤爪を使って木の幹に掴まって、長い切歯を使って木に穴を開ける[20]。そして、浸出物をなめるか、歯で齧って食べる[21]。マーモセットの摂取行動のうちで、こうした植物の浸出物の摂取は20-70%を占める[14][20]。

マーモセットは通年、植物浸出物に食性をおいている。特に1月から4月は果実があまり取れないため、その傾向が強い。マーモセット個体は木の穴を開けるとその後もその穴から採餌する。他の動物が開けた穴の場合でもそれは当てはまる。植物浸出物に加え、昆虫もマーモセットに重要な食物である。食物摂取のための時間を24-30%を昆虫を食べることに当てている。マーモセットは体が小さいため、昆虫だけに頼った食性をすることも可能である。また、体の小ささから昆虫の採取に際しても気付かれずに接近したり待ち伏せすることができる[19]。マーモセットは他には果実、種子、花、茸、花のミツ、カタツムリ、トカゲ、樹住性のカエル、鳥卵や哺乳類の幼獣を食べることが観察されている[21]。このため、マーモセットはオウムやオオハシ、ウーリーオポッサムと果実を競合している可能性がある[21]。

行動[編集]

社会構成[編集]

コモンマーモセットは、大家族で安定した群れを作り、その中で繁殖するのは数匹である[22][23]。マーモセットの群れは15頭程度に上る事もあるが、通常9匹程度である[21]。一つの家族は、1−2頭の繁殖するメス、1頭の繁殖するオス、そしてその子供たちと、さらにその親か兄弟などの大人の親族からなる[23]。群れの中ではメス同士の方がオス同士に比べ、血縁が濃い。オスは、自分の親族であるメスとは繁殖しない。マーモセットは成熟すると生まれた群れを去る事があるが、それは他の霊長類が青年期までには去るのとは対照的である。生まれた群れを去る理由は分かっていない[23]。繁殖するオスが死ぬと、群れは分裂する事がある[24]。群れの中では、繁殖に関わる個体はより優位であるが、繁殖に関わっているオスとメスの間では、優位性は確認し難い。しかし、繁殖に関わっているメスが二頭いる場合は、どちらかがより優位である。この場合、劣位のメスと優位のメスであるのが通常であるが、そのほかの個体間では社会優位度は年齢による[22]。優位性は様々な行動、姿勢、発声を通じて観察され、劣位の個体は優位の個体にグルーミングをする[22]

繁殖と子育て[編集]

複雑な繁殖システムを有する。当初、一夫一妻と考えられてきたが、一夫多妻、あるいは一妻多夫が観察された例もある[22]。それでもなお、多くの例では一夫一妻である。繁殖に関わるメスが二頭いる場合でも、劣位のメスはそのほかの群れのオスと交尾をする事が多い。劣位のメスは繁殖しても子供は状態がすぐれない事が多い[25]。しかし、他の群れのオスと交わる事で、将来的に安定な繁殖相手を見つける事にもつながる。子供を持ったのにもかかわらず、その子が死んだ場合、他の群れに移ってそこで優位な繁殖個体となる場合もある[25]。

繁殖に関わるペアは、子育てに他の個体からの援助を得る必要がある。そのため繁殖に関わる個体は、その他の個体の繁殖を行動的、また生理的に抑制する[26][27]。繁殖が抑制された個体にとっても、通常、繁殖に関わるペアと血縁関係にあることが多いため、遺伝的なつながりがある子を育てることになる[27]。また、血縁関係にあるオスの存在は、メスの排卵に影響する。実験環境下では、父親の存在により娘に当たるメスの排卵が抑制されるが、血縁関係にないオスの場合は、抑制されなかった。また、メスは母親に対して攻撃的態度をとることがあり[27]、その地位を追い去ることもある。

適切な条件下では、成熟したメスは定期的に繁殖し続ける。メスはオスに対して舌を突き出すことで交尾を誘う。妊娠期間は5ヶ月であり、出産後およそ10日で再び交尾ができるようになる。そのため、出産間隔は5ヶ月となり、年2回出産することとなる[21]。マーモセットは通常、二卵性双生児を生む。そのため、妊娠期間と哺乳期間のメスの負担は多く、他個体からの援助が必要となる[17][21]。幼獣は母親の背中に本能的にしがみつき、生後2週間は離れることがない。それ以降は親から離れるようになる[21]。それとともに繁殖に関わるオス(おそらく父親)が世話に参加するようになり、やがて群れ全体がそれに参加する[28]。それから数週間の間、幼獣が母親の背中で過ごす時間は減り、動き回ったり遊んだりする時間が増えていく[21]。幼獣は3ヶ月で離乳する。5ヶ月には若年期に入る。この段階では、両親以外の個体との相互作用が増加する。乱暴な行動も観察され、それが将来の社会的地位につながっていく。次の子供が生まれると、その子供たちを運んだり一緒に遊んだりする[28]。マーモセットは9から14ヶ月の間に亜成体となり、大人としての行動を示し、また思春期を迎える。15ヶ月になると成獣のサイズになり、性的にも成熟するが、社会的に優位にならないかぎり繁殖はできない[28]。

コミュニケーション[編集]

Common marmosets employ a number of vocal and visual communications. To signal alarm, aggression, and submission, marmosets use the "partial open mouth stare," "frown," and "slit-stare", respectively. To display fear or submission, marmosets flatten their ear-tufts close to their heads.[21] Marmosets have two alarm calls: a series of repeating calls that get higher with each call, known as "staccatos"; and short trickling calls given either intermittently or repeatedly. These are called "tsiks". Marmoset alarm calls tend to be short and high-pitched.[24] Marmosets monitor and locate group members with vibrato-like low-pitched generic calls called "trills".[29] Marmosets also employ "phees" which are whistle-like generic calls. These serve to attract mates, keep groups together, defend territories, and locate missing group members.[29] Marmosets will use scent gland on their chests and anogenital regions to mark objects. These are meant to communicate social and reproductive status.[21]

状況[編集]

コモンマーモセットの生息数は数多く、絶滅の危機にあるとは考えられていない。それでも生息域の縮小が加速し、67%のセラードが1990年代に開発され、最近では80%に拡がっている[30]。さらにマーモセットは捕獲されペットとして売られている。マーモセットはペットとしては人気があるが、成熟するにつれ扱いにくくなり、その結果捨てられたり殺されたりしてしまう[31]。コモンマーモセットは医学実験にも用いられる。特に、ヨーロッパでアメリカ合衆国よりも多く使われる[32]。モデル動物としてよく使われる用途は、催奇形性、歯周病、生殖、免疫、内分泌、肥満、そして老化の研究である[32][33]。

ゲノム[編集]

メスのコモンマーモセットのゲノムが2014年に報告され、新世界ザルの中で初めて完全なゲノムがわかった種となった。[11]ゲノムのサイズは2.26 Gbで、21,168遺伝子を含んでいた[10]。文節的重複 英:Segmental duplicationsにより、全138 Mbの of non-redundant sequences (4.7% of the whole genome), slightly less than observed in human[34][35] or chimpanzee (~5%),[36] but more than in orangutan (3.8%).[37]

出典[編集]

- ^ a b c Rylands, A.B, Mittermeier, R.A., de Oliveira, M.M. & Kierulff, M.C.M. 2008. Callithrix jacchus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T41518A10485463. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T41518A10485463.en, Downloaded on 07 February 2018.

- ^ a b Colin P. Groves, Genus Callithrix, Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed), Don E. Wilson & DeeAnn M. Reeder (editors). 2005. Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 129-133.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema naturæ. Regnum animale. (10 ed.). pp. 27, 28 2012年11月19日閲覧。

- ^ 増井光子「キヌザル科」『標準原色図鑑全集 19 動物 I』林壽郎著、保育社、1968年、44-48頁。

- ^ 「マーモセット科(キヌザル科)」『世界哺乳類和名辞典』今泉吉典監修、平凡社、1988年、226-230頁。

- ^ 杉山幸丸、相見満、斉藤千映美、室山泰之、松村秀一、浜井美弥「広鼻猿類」『サルの百科』杉山幸丸編、嶋田雅一イラスト、データハウス、1996年、55-102頁。

- ^ 名取真人「コモンマーモセット」『世界で一番美しいサルの図鑑』湯本貴和全体監修、高井正成監修、京都大学霊長類研究所編、エクスナレッジ、2017年、14-15頁。

- ^ Rylands AB and Mittermeier RA (2009). “The Diversity of the New World Primates (Platyrrhini)”. In Garber PA, Estrada A, Bicca-Marques JC, Heymann EW, Strier KB. South American Primates: Comparative Perspectives in the Study of Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. Springer. pp. 23–54. ISBN 978-0-387-78704-6

- ^ 野元正弘、コモン・マーモセット(小型のサル)の薬理学研究への応用 日本薬理学雑誌 1995年 106巻 1号 p.11-18, doi:10.1254/fpj.106.11

- ^ a b Worley, Kim C; Warren, Wesley C; Rogers, Jeffrey; Locke, Devin; Muzny, Donna M; Mardis, Elaine R; Weinstock, George M; Tardif, Suzette D et al. (2014). “The common marmoset genome provides insight into primate biology and evolution”. Nature Genetics (Online). doi:10.1038/ng.3042.

- ^ a b Baylor College of Medicine. “Marmoset sequence sheds new light on primate biology and evolution”. ScienceDaily 2014年7月21日閲覧。

- ^ Macdonald, David (Editor) (1985). Primates. All the World's Animals. Torstar Books. p. 50. ISBN 0-920269-74-5

- ^ Brandão, Tulio Afflalo (2006年12月). “BRA-88: Micos-estrelas dominam selva urbana carioca” (Portuguese). 2009年4月10日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d Rowe, N. (1996). Pictorial Guide to the Living Primates. East Hampton: Pogonias Press. ISBN 0-9648825-0-7

- ^ Groves C. (2001) Primate taxonomy. Washington DC: Smithsonian Inst Pr.

- ^ Garber PA, Rosenberger AL, Norconk MA. (1996) "Marmoset misconceptions". In: Norconk MA, Rosenberger AL, Garber PA, editors. Adaptive radiations of neotropical primates. New York: Plenum Pr. p 87-95.

- ^ a b c d Kinzey WG. 1997. "Synopsis of New World primates (16 genera) ". In: Kinzey WG, editor. New world primates: ecology, evolution, and behavior. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. p 169-324.

- ^ Rylands AB, Coimbra-Filho AF, Mittermeier RA. 1993. "Systematics, geographic distribution, and some notes on the conservation status of the Callitrichidae". In: Rylands AB, editor. Marmosets and tamarins: systematics, behaviour, and ecology. Oxford (England): Oxford Univ Pr. p 11-77.

- ^ a b c Rylands AB, de Faria DS. (1993) "Habitats, feeding ecology, and home range size in the genus Callithrix". In: 'Rylands AB, editor. Marmosets and tamarins: systematics, behaviour, and ecology. Oxford (England): Oxford Univ Pr. p 262-72.

- ^ a b Ferrari SF, Lopes Ferrari MA. (1989) "A re-evaluation of the social organization of the Callitrichidae, with reference to the ecological differences between genera". Folia Primatol 52: 132-47.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Stevenson MF, Rylands AB. (1988) "The marmosets, genus Callithrix". In: Mittermeier RA, Rylands AB, Coimbra-Filho AF, da Fonseca GAB, editors. Ecology and behavior of neotropical primates, Volume 2. Washington DC: World Wildlife Fund. p 131-222.

- ^ a b c d Digby LJ. (1995) "Social organization in a wild population of Callithrix jacchus: II, Intragroup social behavior". Primates 36(3): 361-75.

- ^ a b c Ferrari SF, Digby LJ. (1996) "Wild Callithrix group: stable extended families? " Am J Primatol 38: 19-27.

- ^ a b Lazaro-Perea C. (2001) "Intergroup interactions in wild common marmosets, Callithrix jacchus: territorial defense and assessment of neighbours". Anim Behav 62: 11-21.

- ^ a b Arruda MF, Araujo A, Sousa MBC, Albuquerque FS, Albuquerque ACSR, Yamamoto ME. 2005. "Two breeding females within free-living groups may not always indicate polygyny: alternative subordinate female strategies in common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) ". Folia Primatol 76(1): 10-20.

- ^ Baker JV, Abbott DH, Saltzman W. (1999) "Social determinants of reproductive failure in male common marmosets housed with their natal family". Anim Behav 58(3): 501-13.

- ^ a b c Saltzman W, Severin JM, Schultz-Darken NJ, Abbott DH. (1997) "Behavioral and social correlates of escape from suppression of ovulation in female common marmosets with the natal family". Am J Primatol 41:1-21.

- ^ a b c Yamamoto ME. (1993) From dependence to sexual maturity: the behavioural ontogeny of Callitrichidae". In: Rylands AB, editor. Marmosets and tamarins: systematics, behaviour, and ecology. Oxford (England): Oxford Univ Pr. p 235-54.

- ^ a b Jones CB. (1997) "Quantitative analysis of marmoset vocal communication". In: Pryce C, Scott L, Schnell C, editors. Marmosets and tamarins in biological and biomedical research: proceedings of a workshop. Salisbury (UK): DSSD Imagery. p 145-51.

- ^ Cavalcanti RB, Joly CA. (2002) "Biodiversity and conservation priorities in the cerrado region". In: Oliveira PS, Marquis RJ, editors. The cerrados of Brazil: ecology and natural history of a neotropical savanna. New York: Columbia Univ Pr. p 351-67.

- ^ Duarte-Quiroga A, Estrada A. (2003) "Primates as pets in Mexico City: an assessment of the species involved, source of origin, and general aspects of treatment". Am J Primatol 61: 53-60.

- ^ a b Abbott DH, Barnett DK, Colman RJ, Yamamoto ME, Schultz-Darken NJ. (2003) "Aspects of common marmoset basic biology and life history important for biomedical research". Compar Med 53(4): 339-50.

- ^ Rylands AB. (1997) "The callitrichidae: a biological overview". In: Pryce C, Scott L, Schnell C, editors. Marmosets and tamarins in biological and biomedical research: proceedings of a workshop. Salisbury (UK): DSSD Imagery. p 1-22.

- ^ Venter, J. C. (2001). “The Sequence of the Human Genome”. Science 291 (5507): 1304–1351. doi:10.1126/science.1058040. PMID 11181995.

- ^ McPherson, John D.; Marra, Marco; Hillier, LaDeana; Waterston, Robert H.; Chinwalla, Asif; Wallis, John; Sekhon, Mandeep; Wylie, Kristine et al. (2001). “A physical map of the human genome”. Nature 409 (6822): 934–941. doi:10.1038/35057157. PMID 11237014.

- ^ and Analysis Consortium, The Chimpanzee Sequencing (2005). “Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome”. Nature 437 (7055): 69–87. doi:10.1038/nature04072. PMID 16136131.

- ^ Locke, Devin P.; Hillier, LaDeana W.; Warren, Wesley C.; Worley, Kim C.; Nazareth, Lynne V.; Muzny, Donna M.; Yang, Shiaw-Pyng; Wang, Zhengyuan et al. (2011). “Comparative and demographic analysis of orang-utan genomes”. Nature 469 (7331): 529–533. doi:10.1038/nature09687. PMC 3060778. PMID 21270892.

外部リンク[編集]

- Common Marmoset Care

- Lang, Kristina Cawthon (2005年5月18日). “Common marmoset: Callithrix jacchus”. Primate Factsheets. Primate Info Net. 2009年4月10日閲覧。

- View the Marmoset genome in Ensembl.